At this stage of James’ Tour of Disco-Era Women SF Authors, we have reached M. Certain letters are deficient in authors whose surnames begin with that particular letter. Not so M. There is an abundance of authors whose surnames begin with M. Perhaps an excess. In fact, there are more authors named Murphy than the authors I listed whose names begin with I. Efforts to address this, by providing authors with exciting new initials, perhaps involving the exclamation mark or ampersand, have thus far been greeted with something less than enthusiasm by the powers-that-be.

For readers who have just joined the tour: there are several previous instalments in this series, covering women writers published in the 1970s with last names beginning with A through F, those beginning with G, those beginning with H, those beginning with I & J, those beginning with K, and those beginning with L.

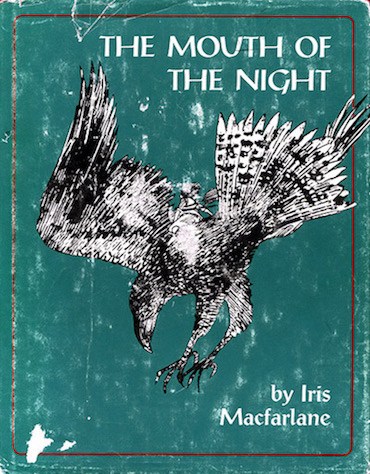

Iris Macfarlane

Iris Macfarlane, by all rights, should be on my List of Shame, which covers those authors I’ve somehow missed out on reading to date. A glance at her ISFDB entry reveals that my ignorance may not matter, as she seems to have had one and only one collection, 1976’s The Mouth of the Night, which makes choosing which of her works to recommend unusually straightforward. The Mouth of the Night appears to be translations from Gaelic to English of stories originally included in J. F. Campbell’s 1890 Tales of the West Highlands. I think.

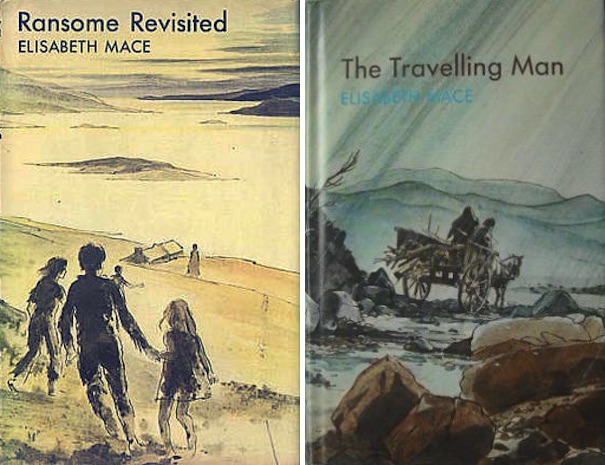

Elisabeth Mace

Elisabeth Mace was the author of a number of young adult novels. The logical starting point for Mace is her 1975 post-apocalyptic young adult novel Ransome Revisited, the first of two books in her Levin sequence…that is, if you can find a copy. If Mace has benefited from the recent wave of ebook reprints, I was unable to find any of hers.

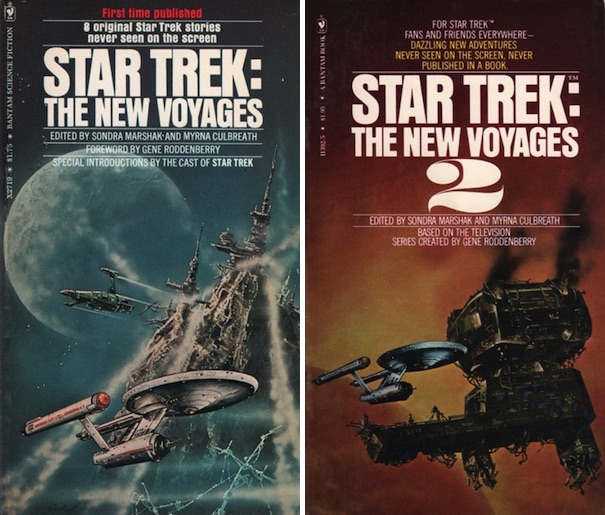

Sondra Marshak

Sondra Marshak is best known for her Star Trek-related activity. Star Trek, an American science fiction television show akin to Raumpatrouille—Die phantastischen Abenteuer des Raumschiffes Orion, was cancelled after seventy-nine episodes in the mid-1960s. An anthology of original stories commissioned a decade after a show’s cancellation seems unthinkable and yet in 1976, Marshak and Myrna Culbreath’s co-edited collection, Star Trek: The New Voyages, was published by Bantam Books, soon followed by Star Trek: The New Voyages 2. This suggests that the show’s fandom managed to survive the show’s demise. Perhaps some day there will be a revival of this venerable program—perhaps even a movie!—although I must caution fans against getting their hopes up…

Fans of John Scalzi’s Redshirts may find the New Voyages story “Visit to a Weird Planet Revisited” of interest, as yet another example of science fiction authors independently hitting on very similar ideas.

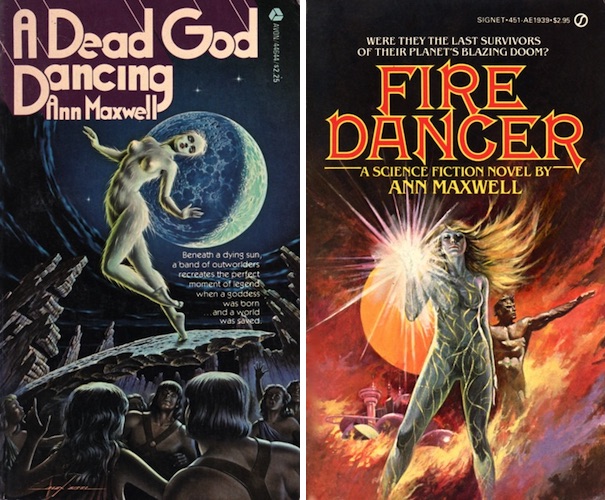

Ann Maxwell

Ann Maxwell’s career might be credited to the fact that there was no internet back in the 1970s (well, no public internet; there was Arpanet for the tech elite). Isolated, without convenient sources of entertainment, and having exhausted her library’s stock of science fiction as one often did in those days, she turned to writing. Prolific and successful, her output these days is primarily in other genres, often published under the name Elizabeth Lowell. I would suggest that SF readers try her 1979’s A Dead God Dancing, a lush pre-apocalyptic novel set on a doomed world1.

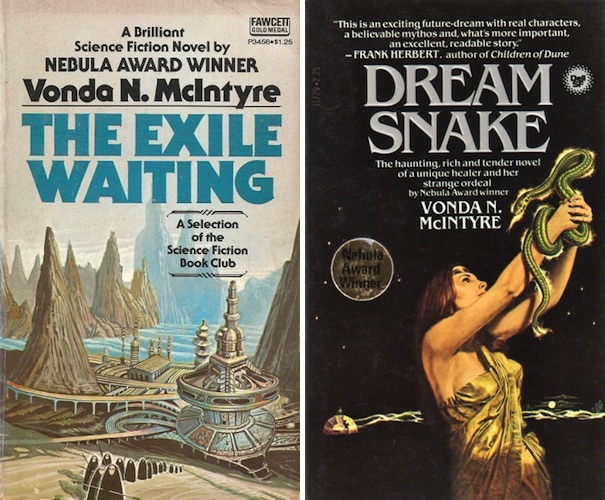

Vonda N. McIntyre

I have followed Vonda N. McIntyre’s career since I encountered her 1975 debut novel, The Exile Waiting. As have numerous other authors, she has dabbled in Star Trek novels, managing the difficult trick of seamlessly adding details to Trek plots in order to patch plot holes in the original episodes. Although my favourite work of hers is her 1979 collection Fireflood and Other Stories, it is long, long out of print. Modern readers should therefore seek out McIntyre’s Hugo- and Nebula-winning post-apocalyptic wanderjahr novel Dreamsnake, in which a wandering healer contends with blind prejudice and self-destructive family conflict.

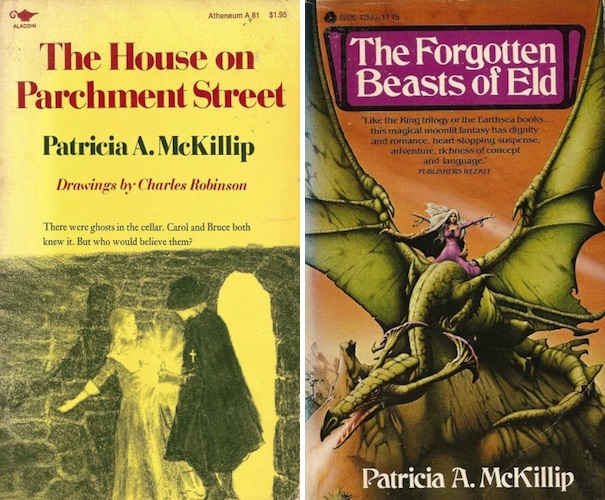

Patricia A. McKillip

Patricia A. McKillip is an author I first encountered thanks to my inability to send back the Science Fiction Book Club forms in a timely fashion (the SFBC assumed one wanted each month’s books unless readers actively told them otherwise). So, sloth for the win! Since her 1973 debut novel The House on Parchment Street, McKillip has written over two dozen novels, garnering World Fantasy Awards, Balrog Awards, Mythopoeic Awards, the Endeavour Award, as well as too many nominations to mention. 1974’s dreamlike fairy tale The Forgotten Beasts of Eld won the following year’s World Fantasy Award, and contemporary readers can enjoy the recent Tachyon reprint.

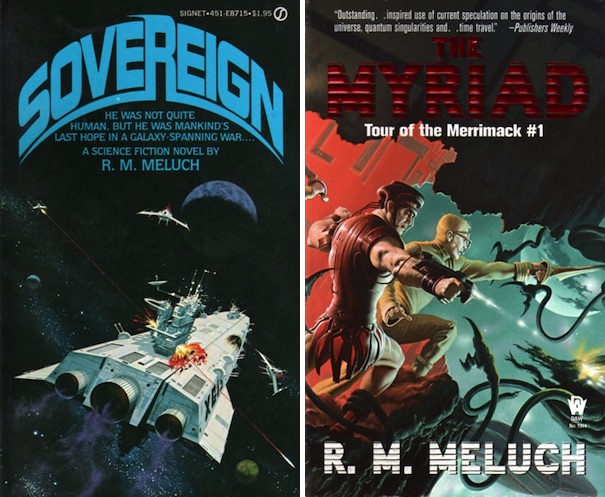

R.M. Meluch

Although R. M. Meluch has been active since 1979’s Sovereign (whose cover looks very familiar to me, even if the plot entirely escapes me), the only works of hers I have read belong to her military SF Tour of the Merrimack series, which pits American and Romans IN SPAAACE against ravening space horrors. Not to my taste, but I know there are respected reviewers who are keen on Meluch’s works (with reservations: see here). The first Merrimack novel is 2005’s The Myriad.

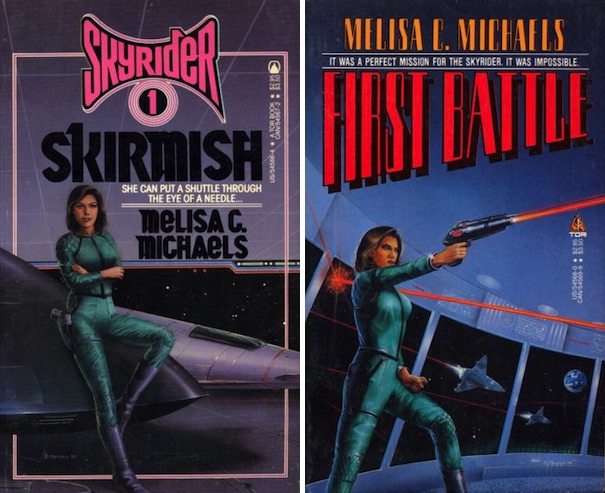

Melisa C. Michaels

Although hard-nosed women action heroes were by no means unknown decades ago, neither were they especially common. Melisa C. Michaels (whose debut story, “In the Country of the Blind,” won a spot in Terry Carr’s The Best Science Fiction of the Year 9) provided one of the relatively few examples. The story belongs in the setting of her Reagan-era Skyrider series. Skyrider’s first instalment was 1985’s Skirmish, in which a talented pilot becomes a pawn in a game whose end phase may be interplanetary war.

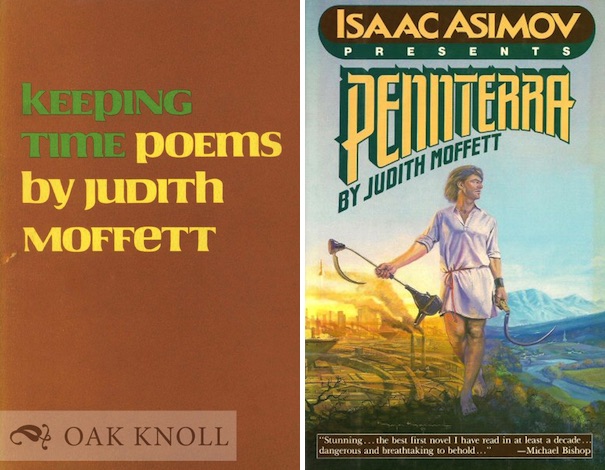

Judith Moffett

Judith Moffett’s 1979 poetry collection Keeping Time may not be genre, depending on who you believe. Wikipedia seems convinced it is not, but ISFDB seems to think it is. That’s enough, IMHO, to warrant including Moffett now (and not in a hypothetical/possible 1980s-focused sequel to this series). Moffett’s 1987 Pennterra presents an alien world settled first by Quakers (who found a way to conform to the native Hrossa’s demands) and later by non-Quakers (who opted for a more confrontational and markedly less successful strategy.) Readers familiar with fellow Quaker Joan Slonczewski’s 1980 Still Forms on Foxfield may notice similarities. Both books feature established Quaker settlers and their alien friends contending with uncooperative Terran latecomers. Moffett, however, takes her novel in a very, very different direction than does Slonczewski.

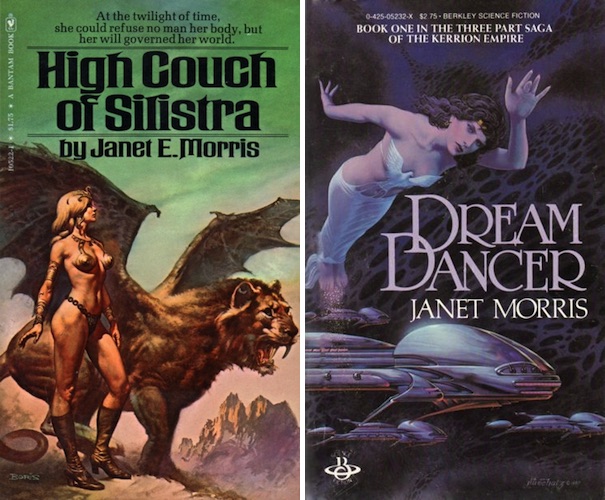

Janet Morris

Readers familiar with Janet Morris’ work may have first encountered it in the 1980s, in that period when Morris was one of Jim Baen’s go-to authors. Morris has published thirty-three novels, fourteen anthologies, and sixty short stories of which I am aware. Of those, twenty-two novels, eight anthologies, and thirty-eight short stories appeared in the 1980s, most of them from Baen Books. I first became aware of her in the 1970s because her BDSM-flavoured planetary adventure novel The High Couch of Silistra. was very well distributed, at least in Canada. Not my thing, again, but your mileage may vary.

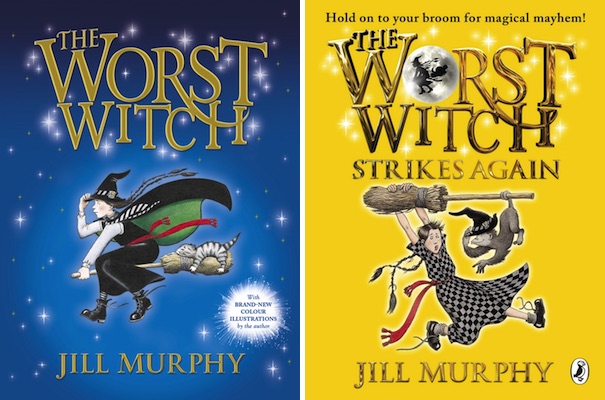

Jill Murphy

Jill Murphy’s career was very nearly done in before it began, thanks to publishers’ trepidation about the idea of trying to sell children’s stories set at a school for youthful magic users2. Nevertheless, she persisted; the result was Murphy’s popular Worst Witch series, whose first book is the eponymous Worst Witch. Tor.com readers may be too old for Murphy’s work, but their children may not be. Or, sigh, their grandchildren. Who came up with this inexorable passage of time thing?

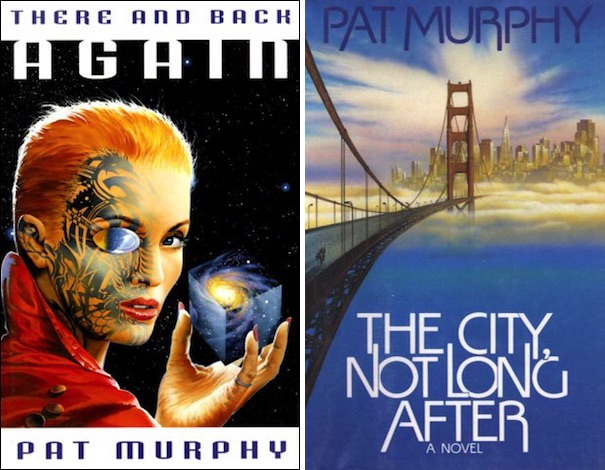

Pat Murphy

As established elsewhere, my favourite James Tiptree, Jr. Award co-founder Pat Murphy’s work is 1999’s There And Back Again, an SFnal reimaging of a certain tale of a reluctant burglar and his diminutive companions. For various reasons, There And Back Again is hard to find. In contrast, Murphy’s 1989 hopeful post-apocalyptic The City Not Long After, which pits a self-aggrandizing warlord bent on conquest against a seemingly defenceless artists’ colony in the ruins of San Francisco, is available from Open Road Media.

* * *

As one might expect from an initial shared by so many authors, this instalment’s List of Shame, those authors I have inexplicably not encountered sufficiently to comment on them, is long. Very long. Excessively long. My apologies to the authors in question. If readers have suggestions where to begin with the following, please feel free to provide them…

- Phillipa C. Maddern

- Sara Maitland

- Joyce Marsh

- Marcia Martin (looking at her ISFDB entry suggests that I have read her fiction and simply forgotten it during the ensuing decades. I’ve made a note to track down something by her. My apologies to the author: it’s nothing personal, just MCI.)

- Gloria Maxson

- Pat McIntosh

- Clare McNally

- Beth Meacham is of course well known to me as a skilled and highly regarded editor. It happens I have not read (or even ever seen) her novel Nightshade, Book One: Terror, Inc. I’ve even owned her Terry’s Universe for years, but I’ve not yet read it. Still, for readers who may not have read her fiction or anthologies, the odds are extremely good they’ve read fiction in print due to her efforts.

- Marlys Millhiser

- Cynthia Morgan

- Rita Morris

- Shirley Rousseau Murphy

1: Which I plan to reread and review as soon as I remember where I filed my copy. Not under M, apparently.

2: I know J. K. Rowling ran into publisher skepticism about the commercial viability of her Hogwarts stories, which appear to have subsequently enjoyed a degree of success. Le Guin’s 1968 A Wizard of Earthsea also focused on a Boy Who Survived and later went to a sorcerer’s school. Did Le Guin suffer the same pushback that Murphy and Rowling experienced?

In the words of Wikipedia editor TexasAndroid, prolific book reviewer and perennial Darwin Award nominee James Davis Nicoll is of “questionable notability.” His work has appeared in Publishers Weekly and Romantic Times as well as on his own websites, James Nicoll Reviewsand Young People Read Old SFF (where he is assisted by editor Karen Lofstrom and web person Adrienne L. Travis). He is surprisingly flammable.